Description

The study of integral anatomy is an invitation to the whole person to study the whole person. Gil introduces us to the series so you know what to expect and then begins the dissection with the first layer, the skin.

This video was filmed and produced by Gil Hedley. Please note that it includes graphic videos and photos of dissections of cadavers (embalmed human donors). You can visit his website for more information about his workshops.

About This Video

Transcript

Read Full Transcript

Greetings. My name is Gil Hedley, and I'd like to thank you for your interest in the Integral Anatomy series. I'd also like to acknowledge your courage for opening this door and walking through it. The study of Integral Anatomy is an invitation to the whole person to study the whole person. By studying human form and the physical human body through the dissection process, we invite ourselves to drop down through the layers and see ourselves reflected there in the depths at every level.

We undertake the dissection process in order to investigate relationships, increase our awareness of continuities, and heighten our sense perception and experience of what lies within us. We also can become aware of our relationship to our bodies. We can use this process as an opportunity to notice our likes and dislikes and move towards an acceptance of the great gift our bodies represent. Beyond mechanistic models, we will look to the intelligence and forms of nature for ways to help us understand the body better. Like astronauts who bravely approach the frontiers of outer space in their quest for discovery, together we will become somanauts, navigating our bodies to the frontiers of inner space.

The imagery contained in the sequences which follow are both extraordinary and intense. I invite you who view this to respect your comfort zones while you work to expand them. It is our common intention to learn from this experience and to share the excitement of discovery. If you study with me in the lab, I bring you slowly into the experience, step by step. The sequences which follow have a similar organization, but it will remain up to you to set the pace, since a DVD permits you to skip this and that, so I encourage you, especially if you are new to the dissection process, to respect where you are and take this one step at a time.

The cadaver is by definition an embalmed body, notwithstanding the value of working with fresh tissue. I prefer to work here with preserved tissue for the following reason. It enables me to demonstrate whole layers which would otherwise be nearly impossible to grasp and present under the time constraints of working with fresh tissue. Physical anatomy is concerned with whole body continuities which are otherwise lost when taking a regional approach. Before entering the lab, let's take a moment now to find in our hearts a place of acknowledgement and thanks for all donors and their families.

We are all the beneficiaries of these precious gifts and through our study and exploration, we honor what has been offered to us and give our appreciation in return. At this point we've opened the humidor and we look upon the skin of an elderly woman's cadaver form and a cadaver is not a person, it's simply a model of the body of a person. I say a model because through the process of embalming, the tissues change in quality and texture and color somewhat and death itself leaves the body at room temperature rather than the way it is in the living at 98.6 and so there are many differences between both a live body and a dead one and a dead body and a cadaver form so here we see the skin of the cadaver form and acknowledge it. The form here appears a bit more taut and round than it would have been in the living person. That is the effect of the embalming process in this particular instance upon this body.

Here we see another form, the form of a gentleman. In this instance the skin has been desiccated rather than stretched taut by the embalming fluid so it gives a slightly different look to the surface presentation. While it's true that the skin of the living is as interesting to study as the skin of the dead, it's part of the process of dissection to observe and acknowledge what we see on the outside and then to come to an understanding of the relationships of course of the skin to what lay beneath it as well as the skin in its depth and complexity from one area of the body to another. So we take the time with the skin of the cadaver even though we can learn so much from the skin of the living through touch and our experience of sensation, there's also much to be learned from the skin of the cadaver form as well. Here we see another female form of slighter proportion for the sake of comparison with the first.

Morphology is a fascinating study and dissection is a road into it. By morphology I mean simply to say the study of shape. So when we look at a given cadaver's form we can ask ourselves the question or when we look at the form of a living we can ask ourselves the question exactly which layer is it that's primarily presenting in a way that defines this person's shape. Is this person shaped by their organs primarily? Are they presenting their superficial fascia and that's what gives them their characteristic shape.

Perhaps they're shaped particularly by their musculature or perhaps they're shaped more particularly by their bony formation or deformation. So when we study anatomy in this way we raise the questions about the layers and it helps us to get a bead on what we're looking at when we view a particular individual shape. Here we'll take a closer look at one particular form, a gentleman's form, as we observe the general tone of skin and we can look more closely and notice on the right there of the image now close up a very common surgical scar, the great saphenous vein has been removed in our country about 400,000 open heart surgeries a year are performed so it's extremely common to observe these types of scarring in the cadavers, more common than not actually. Here observing more closely at the chest we can see a midline incision and over by the shoulder some dried out patches which are not indicative of anything at all. As we look more closely we can just follow up the leg and grow accustomed to the coloration of the tissue, the way it lies, the man is very lean, in this particular instance we can see and we come up close on the belly here, that's a little red patch which we might follow down deeper if we remember it.

Some can't always tell what a color indicates in a cadaver, sometimes we can tell very clearly if something is an artifact here of the surgery, here at the neck area by the clavicle we see the incision of the embalmer, the embalmer has to introduce the embalming fluids and they follow the root of the jugular and carotid vessels. Here the group is gathered around the table and together we make these sorts of observations. And then from observation we move to palpation, feeling the cadaver form, massaging the tissues, discussing with one another what we observe, pointing things out to one another and becoming comfortable in handling the form. In that sense the palpation process serves a dual purpose, both of familiarizing our self with the cadaver and its mobility etc. and also rendering ourselves more comfortable in working with it and then before differentiating we palpate once again. Now skin is an incredibly resilient substance, it's strong, it has fantastic integrity and about the only method I've discovered for differentiating the skin from the superficial fascists use a scalpel, it's always my preference to use the gentlest tool possible and you have to bring the right tool to the right task.

I make a long incision and not very deep, the skin although strong isn't necessarily very thick as we'll see when we begin to lift this section of tissue. So by simply taking my hemostat and grabbing a corner I'm able to pass my scalpel underneath and very quickly find my way to the depth of the layer, I need to determine which is skin and which is superficial fascia. So I identify the superficial projection of the skin, the back of the skin and then the underlying superficial fascia. Once I've identified my layers then it's possible to differentiate them most effectively. If I haven't clarified which layer is which and where the transition of textures is it's not possible to execute the idea of creating superficial fascia man here.

So once I'm clear on the tissue layer then I can feel for it in its integrity as I tug with my hemostat and pass my scalpel blade through the relationships of the skin and superficial fascia. It's not really possible to reflect and remove the skin by hand, the mediation of the instrument is necessary. We can see a little bit of superficial fascia there on the back of the skin and then as we create some tension, as I create a tension on the tissue it's possible to see the relationship of the skin to the superficial fascia which I then pass my blade through sometimes even dividing the skin itself and create those tensions and give a tug and then it's possible to say yes I've got the skin and to proceed with the project further. As a larger area is exposed then it becomes possible to make observations within the superficial fascia itself and there we can start to see tiny little blood vessels evident at this borderland where the skin and superficial fascia meet. Taking a larger view of this reflected skin we can see clearly the two different layers demonstrated, layers that just moments ago were united in an integral human form.

Dissection of the entire human skin is really a team effort and when a group gets together there's a certain intensity and focus in the air that seems to give evidence of the quality of skin itself on ectoderma layer noted by Dean Juwan beautifully as the surface of the brain, the skin in a very real sense is the surface of the brain, it's periphery of sensing. It's also remarkable in my opinion to take the opportunity to compare the skin of the living and the skin of the cadaver, often times we imagine that our life force is most readily witnessed in our eyes and yet here it's powerfully clear that the life energy and life force pulses forth from our living skin and it's a stark comparison with that of the cadaver skin. Each area of the body presents its own challenges for the disector, curved surfaces can be more challenging than relatively flat ones and at the same time we also take note of different thicknesses of the skin, it's thin by the shin, thicker by the shoulder and all of these present challenges for the disector. Now at this point in the dissection progression with this particular form we've moved past observation, palpation and differentiation, we're at the point where we can reflect the skin as a whole, it's an exciting moment for the group as we reveal to you superficial fashion man, a creature just beneath the surface of the skin, the skin ultimately is like a mask layer, it hides a more vulnerable creature just beneath its surface, it's a rare vision to be able to see superficial fashion man in his entirety. We have a series of cadaver forms now with their skin on and then with the skin reflected and removed.

In this way we can demonstrate in fact the skin as a whole body layer and then immediately beneath it the superficial fascia as a whole body layer, of course we'll inspect the superficial fascia more closely in the sequence on superficial fascia. But for now we just take in the vista of the cadaver form with skin on and with skin off. The scalpel blade goes dull in this effort because really the skin doesn't want to be separated, the skin is the skin of the body, it represents the periphery of the vascular and neural trees so it's as if we've cut all the leaves off of a tree in full foliage in that sense, in that we've taken away the peripheral endpoints and in doing so in severing those relationships and disrupting that union many scalpel blades go dull in the process of differentiating, reflecting and removing the skin. There can be no doubt in our minds however at this point of the unity of skin in itself as a layer as well as its intimate relationship with the superficial fascia immediately beneath it as the next textural layer. Now in keeping with the dissection progression the time comes when having not only reflected and removed the skin we have the opportunity to dissect further to observe and palpate the skin as an independent structure, a new creation, the first time a skin unto itself and so here we see the skin held aloft by the group, we're looking at the outer surface of the skin, the back is in the center, the legs hanging down like boots, the arms and head and neck region held aloft.

It's a profound sight, it's heavy and completely compelling for the group's observation. Seeing the skin in this way prompts us to consider as many functions as well. The skin of course serves at some level as a barrier, has its immune function, we are protected by our skin from the intrusion of substances without into our bloodstream. At the same time the skin is permeable, we can excrete through our skin and in doing so we regulate our temperature and our salt content of our body etc. and at the same time it's permeable in the other direction so that we can see clearly demonstrated here how light can pass through at certain frequencies of the electromagnetic spectrum and when we see that we can consider what the interactions might be of that light with our skin and with our physiology within. Of course we know that vitamin D is formed in our skin through its interaction with light.

We might also consider comparing the blood flow, our entire blood supply flows through our eyeballs about every two hours and that exposes our blood to the ultraviolet frequencies and their cleansing properties and certainly has an important immune function and is important for our health and we should all admit ourselves to the sunlight at least two hours a day to assure that our blood is cleansed in that way. At the same time we can see that the skin being the outermost peripheral terminus of our neurovascular trees, that makes us wonder what could be the additional interactions that are taking place, the healthful interactions of light at the level of our skin with our nervous and vascular trees. Also because skin is a road both in and out of our bodies we can also recognize when we notice the permeability of a certain electromagnetic frequencies that the electromagnetic frequencies that are generated within us can also extend past our skin. So while the skin defines our bodies visually to the normal and non clairvoyant sense our heart waves and our brain waves and goodness knows our liver waves too can certainly project themselves beyond the skin and it's that fact that enables us to use an EKG or an EEG to sense those waves permeating through our skin and to our surrounding environment and imprinting our surrounding environment with the wavelengths of our habitual patterns of being. Now we'll take a closer look at the skin, here there's a patch of skin prepared for our observation, it's positioned as it was in the form originally although all of its relationships have been severed so that we can reflect it back and flip it over and look at the skin close up.

The patterns that we observe on the back of the skin here are common through much of the body where the skin has some substantial thickness at places where it's very much thinner say at the eyelid or at the shin we won't find this kind of patterning which looks very much like the surface of cantaloupe although in the skin it represents an elastic stretchy fabric which conforms to all of the complex movements of the underlying structures. It's quite amazing how this living fabric is able to constantly conform to elongate and to contract back with the elongation of our form at large. We take a closer look then at the edge of the skin we can see its thickness here in cross section, perhaps a few millimeters. Skin can be quite thin sometimes say again at the eyelid maybe only one millimeter thick. Here it's several millimeters and at the shoulders sometimes can be even twice this thick.

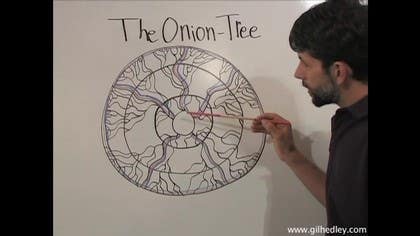

Underlying the skin the superficial fascia reflects the patterning that we see on the back of the skin the bubbly matrix of the superficial fascia meets up with the complex web of the skin. It's those relationships that we severed already and it's through this superficial fascia that the neurovascular trees perforate and reach out and stretch to their utmost periphery in the skin where blending heart and neural tree together they form this complex web of nourishment and sensitivity combined. That rich combination is the inherent nature of our skin. We will discuss this in another video while you So, here we have our onion and tree model on the whiteboard, and let's explore it a little. On the periphery here, we see a ring, and then another ring, more centrally, and another ring, and another ring.

So we have the rings of our onion, and then we have the branches of our tree embedded and reaching out throughout the layers of the onion. Now of course, this is intended to represent an analogy to the human form. So we'll explain these layers then, and these branchings. Of course, we have our legs here and our arms, and this would represent our head, of course. And then the rings themselves each represent layers of our form.

So we have our skin at the outermost periphery, the outer layer of the onion. And then we have, let's call that a membranous layer, or a flat layer, or maybe a planar layer, or something like that. This outermost layer, and these also. And then here we have, let's call this a fluffy layer, because it's kind of wide and fluffy. So here we have our skin, a flat membranous layer, and then we have this fluffy layer of this superficial fashion.

And then look, we encounter again a membranous layer, just like in an onion, and we'll call that our deep fashion, which underlies our superficial fashion and coats our musculature. So this fluffy layer then here, this broad, wide layer, would represent our muscle layer, our muscle tissue. And deep to that, well, we have of course the bags that surround our viscera, the bags around our organs, whether they be fibrous bags or cirrus membranes, that we'll investigate when we get on to the viscera in further DVDs. But for now, we'll just indicate that there is this sort of flat planar membranous layer surrounding our organ tissue, which would be represented by this fluffy layer. So we have our skin on that ring, our deep fascia, and the bags around our organs here.

And then, betwixt these planar layers, we have our superficial fascia, our muscle layer, and our organs. So now let's study our tree. So if this were to represent the brain, then here, then the branchings of the brain from the center to the periphery, here we have all these nerves coming off, following our limbs, as it were, just like a tree. And those nerves will be penetrating each layer and contacting each layer on their way out to the periphery, at which point they become so complex and substantial that they actually comprise the ring itself almost. The same can be said for the heart, the whole heart, when understood that way, where it starts here at the center, and then branches out, following these pathways of the limbs, out to the periphery, in greater and greater complexity, right along with the nervous tissue.

So our neurovascular trees are traveling out from the center to the periphery, and as they do so, they do two things. They perforate and contact the layers along the way to the outermost ring, and also they become more and more complex and smaller. So the branches become tiny out on the periphery, whereas they were trunk-like at the beginning. So this is something we'll notice while we do dissection as well, that the deeper we go into the form, the bigger the branches get, and we'll start to collapse. As we looked at the superficial fashion and superficial projection, when we just peeked underneath the skin, we saw these tiny little blood vessels.

As we go deeper, as we look into the superficial fashion itself, as we look beneath it, we'll begin to see that the perforating vessels start to get larger and larger until we find ourselves at these great trunks, like the aorta, on our way back to the center of the tree, of the heart tree. And the same goes for the nervous system, of course, as we find our way back to the trunk of that tree, the spinal cord. So here's the onion tree model. It's a simplification. That's our intention, is to provide a simplification from nature that creates helpful analogies in our understanding of the human form so we can explain what we see to one another.

Integral Anatomy: The Integral Anatomy Series

Comments

You need to be a subscriber to post a comment.

Please Log In or Create an Account to start your free trial.